What's next for India-China conflict as Xi Jinping begins third term as President

Will India and China reach a permanent resolution regarding border disputes or will there be a rise in incursions as Xi Jinping assumes his third term as President?

- Undercurrents of tensions between India and China remain after the Galwan clashes

- Xi Jinping has been re-elected as President for a third term

- PM Modi and Xi Jinping briefly met in-person at the G20 Summit after the 2020 clashes

The India-China border situation seems to have come to a standstill but undercurrents of tensions between the two nations remain. Two years on from the Galwan clash in 2020, Prime Minister Narendra Modi and Chinese President Xi Jinping have not had a bilateral meeting. At the recent G20 Summit, they managed a face-to-face interaction but a short one, only to exchange pleasantries.

As Xi Jinping takes reign as Chinese President for a historic third term, it will become important for India and China to come to a permanent resolution regarding border disputes. This is in view of Xi’s expansionist policies and border construction projects have already begun invading India’s territories. Xi Jinping harbours an ambition to expand China’s influence on the global stage and has consolidated power for another 5 years to propel his plans to fruition.

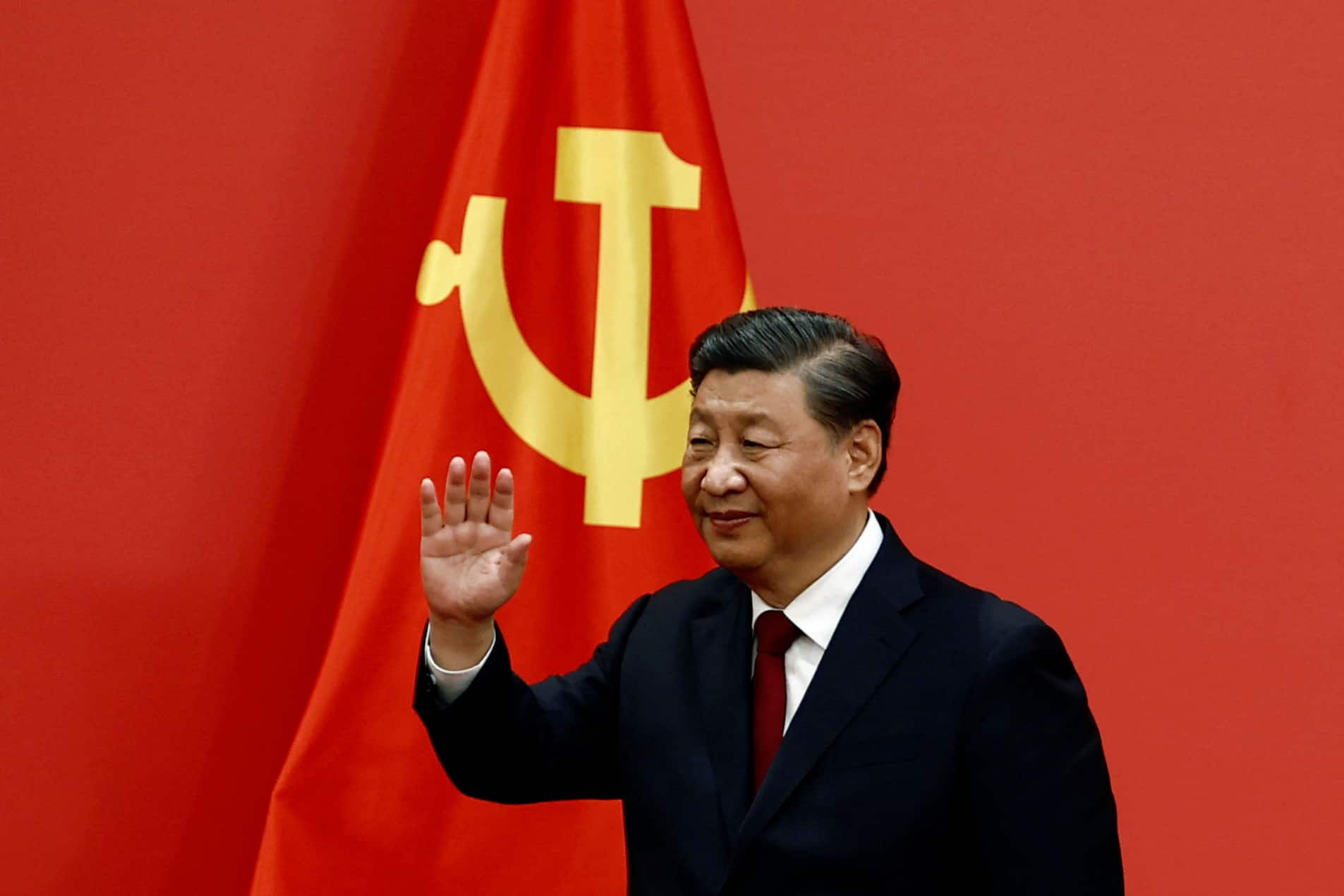

(Image credit: Reuters)

To better understand what Xi Jinping’s third term means for India, Zee News Digital spoke to Mohamed Zeeshan, a policy analyst and Editor-in-Chief of the Freedom Gazette and Byron Chong, a Research Associate at Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy.

How will Xi's territorial expansionist policies affect India?

Mohamed Zeeshan, Editor-in-Chief of the Freedom Gazette and a policy analyst, described the Galwan clash as part of Xi’s invasion of Indian territory. He explained that it is unlikely that talks between India and China will restore the pre-Galwan status quo.

Speaking about Xi’s Himalayan strategy, he said, “Xi's Himalayan strategy isn't entirely different from what he has been doing for years in the South China Sea - gradually expanding China's claims by building and militarising islands, and reinterpreting where their coastlines begin so that China can claim larger areas of the sea surrounding them. He is essentially trying to legitimise China's controversial territorial claims by capturing small bits of them slowly and steadily.”

(Image Credit: Reuters)

Byron Chong, a Research Associate at Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy, expressed similar thoughts, saying – “Beijing will double down on its assertive policies towards other states in the region, including India.”

He also stated that there has been no real indication from Beijing that it regards the repair of bilateral ties with India as a matter of urgency.

Chong made an important observation -- highlighting the promotion of 3 PLA generals, part of the Doklam and Galwan crises, to top posts. “This may be an ominous indication that Beijing expects more clashes along the China-India border and wants military commanders with the requisite experience in charge,” he added.

Will Xi's focus to modernize its military pose a threat to India in future?

It depends on how Xi intends to use his modernised military, explained Zeeshan.

(Image Credit: Reuters)

“If Xi intends to use his modernised military for territorial expansion purposes, India will most certainly be in the firing line. But if Xi decides to ease up on his neighbours and focus instead on larger goals - say, the rivalry with the US in global governance or the quest to build a Chinese-led world order - then, India's equation with China will depend on how far the two countries are able to align on these broader global objectives,” he stated.

Does China consider India to be an emerging global power?

Prime Minister Modi has reiterated India’s rise into becoming a global power in recent years. However, Zeeshan stated that “there’s no public evidence” of Chinese policymakers holding this notion.

“It does seem likely that China sees a US-aligned India as a threat, which would explain China's repeated statements against the Quad and India's participation in it,” he explained.

“Another reason behind China’s border incursions could be to keep India preoccupied on the border dispute and thereby disallow it from playing a wider, more proactive global role,” he proposed.

In addition, Zeeshan said that India has not “set out a coherent policy framework for itself on these sensitive political questions.”

“So, China hasn't really been forced to sit up and take note of India's role on the world stage,” he concluded.

It has often been said that there is a mutual distrust between China and India. Will this distrust widen in Xi's upcoming term?

According to Zeeshan, the mutual distrust could widen, given the fact that Xi now “has the license to be more reckless and aggressive” to achieve his “nationalist goals.”

Meanwhile, Chong attributed China’s distrust of India to the strengthening US-India strategic partnership. “China fears the prospect of facing the US navy at sea and the Indian military along its southern border and in the Indian Ocean—a scenario that became much more real and dangerous when it sees security cooperation between India the US strengthening,” he said.

On whether China and India’s similar stance on the Russia-Ukraine war will improve relations, he said, “The conflict is unlikely to have this effect.”

How will Xi's partnership with Pakistan affect India? Will it mean India strengthening its ties with the US?

Chong said that China’s partnership with Pakistan has been at the fore on the political front as it continues to refuse to black-list Pakistan-based terrorists at UN forums. But there are cracks in the partnership.

“There has been growing criticism of Islamabad’s involvement in the Belt and Road Initiative, which has been seen as one of the major contributors for Pakistan’s ballooning international debt, as well as the mounting economic crisis in the country. Beijing too appears to be less forthcoming than before at providing Islamabad with financial assistance,” he said.

Can the US side with Pakistan instead of India? Chong casts doubt on where America’s loyalty lies and says, “There have been recent moves by the West to woo Pakistan away from China.”

He reasoned saying, “Pakistan was recently removed from the FATF’s ‘grey list’ on terror-funding, allowing it to more easily secure funds from the IMF and World Bank. And US President Joe Biden reversed the Trump administration’s decision to halt security assistance to Pakistan, announcing a $450 million F-16 fighter jet fleet sustainment programme for the country.”

Zeeshan also raised questions on the longevity and sustainability of Pakistan and China’s relationship. “China doesn't seem to have the economic capacity to bankroll debt-ridden regimes forever and we've already seen one sign of failure in Sri Lanka,” he said.

What is the perception of India and Indians among Chinese citizens under Xi?

While China and its policies are a focal point of debate in India, it isn’t the same there, according to Zeeshan. “The state-controlled media has often depicted India as a naive US lackey or as a corrupt and dysfunctional democracy,” he added.

(Image credit: Reuters)

The latter description comes from, Zeeshan explained, a desire of the Communist Party to show that the Chinese system is more effective in delivering growth.

“But if India can create growth and at the same time revive its secular, multicultural democracy, then that would be a serious strategic threat to the CCP - both at home and abroad,” he added.

How do Chinese citizens feel about the growing presence of the CCP in every sphere of their lives?

The Chinese media is largely controlled by the state, thereby swaying public opinion. This may be perceived as restrictive by most liberal, free-thinking individuals. However, Chong argued that most Chinese do not view it as a bother.

“Many Chinese see the strong authoritarian rule as a form of stability, and credit it with China’s economic achievements—large-scale poverty reduction, infrastructure development, and a world-class leader in technological innovator,” he explained.

The Chinese accept the surveillance and exertion of power as a social contract in exchange for stability and development, says Chong.

On the other hand, Zeeshan felt there is a section of Chinese citizens quietly revolting against the repressive policies of the CCP. For instance, when protest banners against zero-Covid policy measures were displayed days before the 20th CCP Congress in Beijing.

“There were reports of an exodus of young Chinese folks and wealthy billionaires out of China after the latest urban lockdowns because owing to Xi's centralisation of control, there is a lot of uncertainty about longer term policy,” he added.

Does China view India as a strategic partner, threat or merely a neighbour?

The Chinese worldview has historically seen neighbouring countries as subordinates. Zeeshan gave a possible explanation for this “condescending” outlook. He said, “The Chinese emperor often saw his kingdom as the centre of the universe and neighbouring states often paid tribute to him.”

Chong posits a similar stand and says, “Their vision for Asia is strictly hierarchical—China sits at the top, and India is not seen as an equal.”

“Despite this, China recognises India’s long historical influence in South Asia and growing capabilities as a regional power. Moreover, by virtue of its sheer size, India has the potential to emerge as a dangerous rival in the future. Thus, China’s policy toward India has focused on balancing India in South Asia by propping up Pakistan and developing ties with small countries in the region,” he added.

(Image credit: PTI)

This does not mean that China wants to sever ties with India as that could mean “exposing China to the US in the Pacific” says Chong.

“Notably, China’s perception of India changed somewhat after the Doklam confrontation. Beijing was surprised by New Delhi’s assertiveness during the clash, and was forced to reassess its previous view of India’s inferior status in the regional power hierarchy,” he adds.

How strong are the cultural ties between China and India?

Cultural ties between people are crucial in creating a deeper social and intellectual connection which, in turn, creates a mutual understanding. While the cultural exchange between India and China had been on the rise - post the 2020 clashes, it went downhill.

“Some Chinese investment has exited India since then and there was a bit of a stalemate recently over the status of Indian students who were studying in China and were left in limbo by Covid-era restrictions,” Zeeshan explains. At the time of the border conflict, Indian sentiments toward the Chinese evidently soured and Chinese media strengthened its anti-media stance through strongly-worded op-eds, and articles. It remains to be seen if Xi’s third term will witness any improvements in people-to-people relations.

Stay informed on all the latest news, real-time breaking news updates, and follow all the important headlines in india news and world News on Zee News.

)